Ghana Northern Region is one of the sixteen regions of Ghana. It is located in the north of the country and was the largest of the sixteen regions, covering an area of 70,384 square kilometres or 31 percent of Ghana’s area until December 2018 when the Savannah Region and North East Region were created from it.

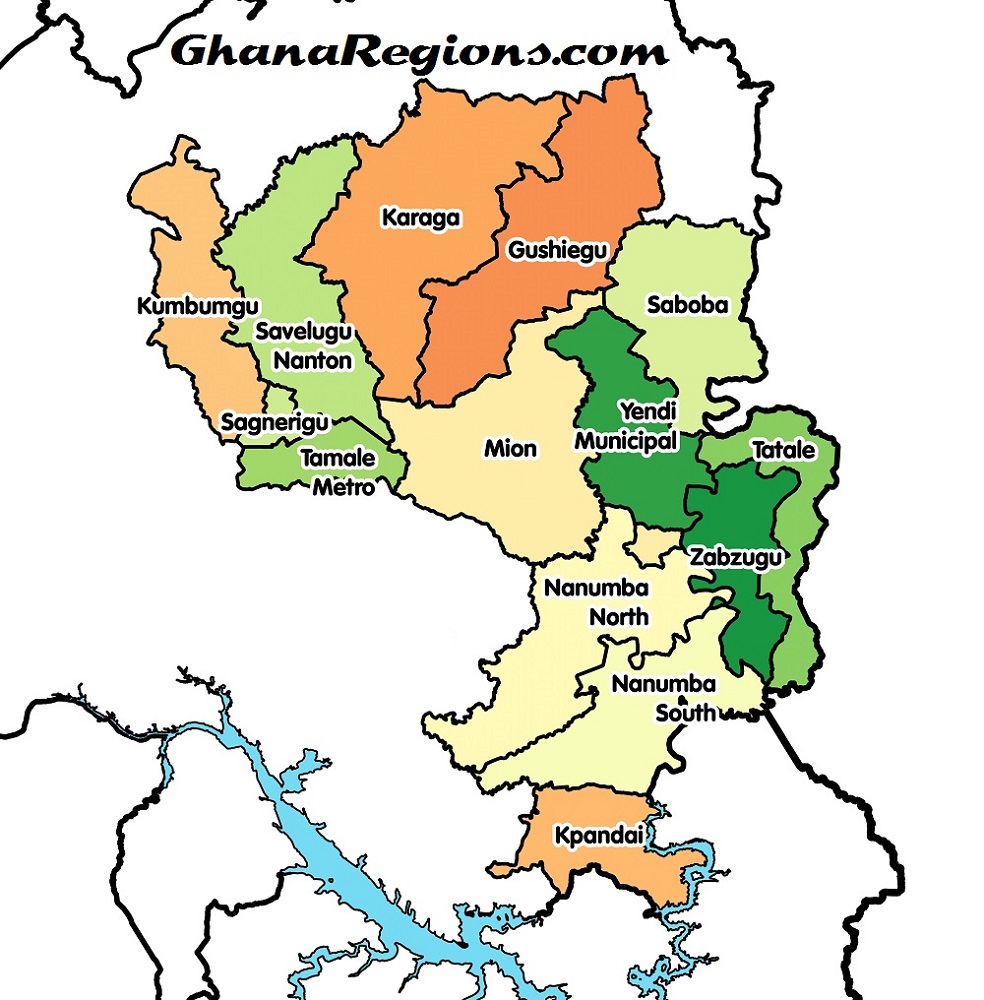

The Northern Region is divided into 14 districts. The region’s capital is Tamale.

The Northern Region, which occupies an area of about 70,383 square kilometres, is the largest region in Ghana in terms of land area. It shares boundaries with the Upper East and the Upper West Regions to the north, the Brong Ahafo and the Volta Regions to the south, and two neighbouring countries, the Republic of Togo to the east, and La Cote d’ Ivoire to the west.

The land is mostly low lying except in the north-eastern corner with the Gambaga escarpment and along the western corridor. The region is drained by the Black and white Volta and their tributaries, Rivers Nasia, Daka, etc.

Climate and vegetation

The climate of the region is relatively dry, with a single rainy season that begins in May and ends in October. The amount of rainfall recorded annually varies between 750 mm and 1050 mm. The dry season starts in November and ends in March/April with maximum temperatures occurring towards the end of the dry season (March-April) and minimum temperatures in

December and January. The harmattan winds, which occur during the months of December to early February, have considerable effect on the temperatures in the region, which may vary between 14°C at night and 40°C during the day. Humidity, however, which is very low, mitigates the effect of the daytime heat. The rather harsh climatic condition makes the cerebrospinal meningitis thrive, almost to endemic proportions, and adversely affects economic activity in the region. The region also falls in the onchocerciasis zone, but even though the disease is currently under control, the vast area is still under populated and undercultivated.

The main vegetation is classified as vast areas of grassland, interspersed with the guinea savannah woodland, characterised by drought-resistant trees such as the acacia, baobab, shea nut, dawadawa, mango, neem.

Political administration

The region is divided into thirteen (13) districts. A Municipal/District Assembly headed by a Chief Executive administers each district. Two-thirds of the members of the Assembly are directly elected. The remaining one-third are appointed by the Central Government. The districts are autonomous with regards to planning and budgeting of projects.

The Assembly is presided over by a Presiding Member elected from among its members by a two-thirds majority of members present and voting. All Members of Parliament from the District are ex-officio members of the Assembly District. The following five new districts were created in 2004 to bring the total number to 18 districts in the region.

The main administrative structure at the regional level is the Regional Co-ordinating Council (RCC), headed by the Regional Minister. Other members of the RCC include representatives from each District Assembly, regional heads of decentralized ministries, and representatives of the Regional House of Chiefs. The Regional Coordinating Director acts as the secretary to the Council.

Cultural and social structure

The region has four paramount chiefs, namely: the Yaa Na based in Yendi; the Yagbon Wura in Damango; the Bimbila Naa in Bimbila; and the Nayiri in Nalerigu. Each represents a major ethnic group. The major ethnic groups of the region are the Mole Dagbon, (52.2%) the Gurma, (21.8%) the Akan and the Guan (8.7%). Among the Mole-Dagbon, the largest subgroup are the Dagomba and the Mamprusi, while the Komkomba are the largest of the Gurma, the Chokosi of the Akan and the Gonja of the Guan. The Dagomba constitute about a third of the population of the region.

The indigenous languages spoken by the people vary from district to district. The Gonja language is spoken mostly in three districts, namely East Gonja, West Gonja and Bole. Dagbani, the language of the Dagomba, is spoken in nine of the thirteen districts. The Kokomba language is spoken mainly in some parts of Saboba-Chereponi, Zabzugu Tatale, East Gonja and Nanumba, Districts. More than half of the population of the region (56.2%) are Muslims. The rest are largely adherents of Traditional religion (21.3%), Christians (19.3%) and other religious groups (3.3%).

Historical and tourist attractions

The Mole National Park, in Damango, West Gonja District, is a 4840 square kilometre reserve for animals such as elephants, buffaloes, wild pigs, antelopes, apes, birds and about 400 other species. The park has a motel with a restaurant, a bar and a swimming pool. This park, which is serviced by Forest Rangers, can best be visited with maximum satisfaction in the dry season.

Tamale, Daboya, Sabari, Nasia, Mole, Bui, among others, have exotic birds suitable for bird watching for pleasure. The savannah vegetation has a scenic beauty of its own, interspersed with rare species of flora and fauna. Baobab trees and ant-hills are part and parcel of this savannah natural vegetation of the region. Other aspects of the savannah scenery and views are the Nakpanduri and other hilly areas of the northern parts of the region, particularly the Gambaga Escarpment.

Shrines and groves

There are sacred groves that are traditional nature reserves created around shrines. Notable among them are the Jaagbo and Malshegu Sacred Graves. The Jaagbo Shrine, situated at 30 kilometres from Tamale, consists of about 25 acres of conserved and preserved vegetation of medicinal herbs and near extinct and mysterious plants around the Jaagbo fetish. Among the vegetation of the grove is the “mystery tree” with marks of the hooves of a horse. The Malshegu Sacred Grove is at Katalga, about 12 kilometres from Tamale.

Architecture, archaeology and culture

The region is well known for its peculiar architecture of round huts with conical thatched roofs, which provide a particular scenic view. Among the relics of the past, which throw considerable light on the history of the people of the region, are the archaeological sites at Yikpa Bonso, in the West Mamprusi District, with relics of the Komas dating back to the nineteenth century (19th C). Other relics of interest in the region are at Jentilkpe and Kpaesemkpe.

Ancient mosques

Ancient mosques are a particular aspect of the relic legacy of the region which under pin the long history of Islam in the region. The Larabaga Mosque, which is of Sundanese architectural origin, dates back to the 13thC but the Bole Mosque, also of a similar Sudanese architectural origin, was built later.

While the Banda Nkwahta and Malew Mosques were built in the 18thC, imitating older mosque designs, the Zayaa mosque in Wulugu, is not only of the 20thC but is peculiar in that it is an uncommon storeyed traditional design of historical and military interest.

The remains of an ancient defence wall are in Nalerigu, in the East Mamprusi District. What is interesting about this defence wall, which dates back to the 15thC, is not only that it was built by a powerful Mamprusi Chief but equally important, is that the wall was built with mortar of mud blood and honey.

Graves

While Mosque relics under-pin the in prints left behind by Islam, graves are reminiscent of battles fought year in the region. There is a mass grave of fallen Dagomba warriors at the battle ground at Adibo, near Yendi, where the Dagombas fought the Germans. The grave of Naa Attabian, a great Mamprusi King, is at Nalerigu, in the East Mamprusi District, while that of Ndewura Jakpa, the greatest King of the Gonjas, is in Buipe, in the West Gong a District.

The graves of massacred Gonjas, have now become shrines at Jentilkipe, where the Gonjas battled with Samore and his army of slave raiders. Evidence of the region being both an important source and route of slaves, abound in the region. Just as the castles are vivid reminders of the departure of the slaves for their unknown destinations in the Diaspora, Yendi is the real archive of important relics of the slave trade, as manifested in the grave of Babato and the relics of his army.

Salaga, where the wells that provided water for bathing slaves for sale, still stand together with the residences of slave merchants, is a vivid reminder of this barbaric trade in human beings.

Myths

The mythical stone, which compelled the construction of a road to be diverted because it could not be removed, is still at Larabanga while a mystery tree with the mark of horse hooves turned up and down is in the Jaagbo grove, near Tawak. Another mystery tree is in the Regional Hospital ground in Tamale.

Festivals

The most important traditional festival in the region is the Damba, a relic of Islam, which has lost its religious origin of the celebration of the birthday of Prophet Mohammed. The Damba celebration is also a mix of music, dance, excitement, horsemanship and regal pageantry, at the climax of Naa Damba. The region is the home of the Fugu textile, the centres of production being Tamale, Gushiegu and Yendi.

Demographic characteristics

The population of the region is 1,820,806, representing 9.6 per cent of the country’s population. This translates into a growth rate of 2.8 per cent over the 1984 population of 1,162,645. This rate of growth is much lower than that of 3.4 per cent recorded between 1970 and 1984.

The World Fertility Survey estimated the total fertility rate (TFR) of the region at 7.9 in 1979/1980. The Demographic and Health Surveys of 1993 and 1998 also estimated the regional TFR at 7.4 (1990) and 7.0 in (1995), suggesting a relatively little decreasing fertility over the period. 4.9, which is significantly lower than the picture presented by the DHS figures; this may be a reflection of fertility reducing programmes in the past decade.

In sharp contrast to the relatively high level of fertility, child mortality has reduced substantially. In particular, the under-five mortality rate has dropped from 237 deaths per 1000 live births in 1993 to 171 deaths per 1000 live births in 1998 (GDHS, 1993; 1998)3. The observed reduction in the rate of growth is the combined effect of the decreasing fertility level, decreasing but still high mortality and increased migration to the south of the country. More than half of the population (50.8%) is in the dependent age group, compared to about 47.0 per cent for the nation as a whole.

The sex ratio for the region as a whole is 99.3 males per 100 females. About 62 per cent of the adult population of the region are married. About one-fifth of the female population, aged 15 years and older (19.3%), have never married. About 73.0 per cent of the population of the region are rural. At the regional level, four out of every five adults are illiterate.

Economic characteristics

Agriculture, hunting, and forestry are the main economic activities in the region. Together, they account for the employment of 71.2 per cent of the economically active population, aged 15 years and older. Less than a tenth (7.0%) of the economically active people in the region are unemployed.

The private informal sector absorbed 83.4 per cent of the economically active population. An additional 11.5 per cent are in the private formal sector leaving the public sector with only 4.3 per cent. Majority, (40.5%) of the 251,221 the not economically active are homemaker and just under a quarter (24.4%) are students. Those who are not working because of old age constitute 14.8 per cent. A small proportion is not working because of disability (2.2%) or are pensioners who are on retirement (1.2%) while 16.9 per cent are classified as others. These rates relate to the 10-year period preceding the surveys.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Introduction

This chapter describes the population distribution of the region by district and by sex. It also presents data on the density and the degree of urbanization at both the regional and district levels. Data on sex ratios are presented together with current levels and trends in the components of population growth and change, particularly fertility and mortality levels. The chapter also discusses the extent of district level migration as measured by the proportion of individuals who continue to reside in their district of birth and the proportion of people born elsewhere, who currently reside in a particular district.

Population size and distribution

The Northern Region is the largest of the 10 regions of the country in terms of landmass, occupying 70,384 square kilometres and accounting for 29.5 per cent of the total land area of Ghana. It has almost the same land area as the Western, Greater Accra, Volta and Eastern Regions put together (28.1%) or the Brong Ahafo, Ashanti and Greater Accra Regions combined (28.2%). Yet, apart from the two Upper Regions, the Northern Region’s population is almost the same as that of Brong Ahafo and slightly larger than that of the Volta and Central Regions, which are much smaller in land area.

The region currently has a population of 1.820,806, representing 9.6 per cent of the total population of the country. This population size is the result of an increase from 531,573 in 1960, through 727,618 in 1970 and 1,164,583 in 1984. These translate into an increase of 36.9 per cent for 1960-1970, 60.1 per cent for 1970-84 and 56.3 per cent for the 1984-2000 periods.

The most spectacular relative increase, 60.1 per cent, occurred during the 1970-1984 period, which also translates into the highest growth rate of 3.4 per cent per annum, during the 1970 -1984 period. This trend also reflects a negligible increase of 1.7 percentage points in the region’s share of the national population over a 40 year-period, 1960-2000.

The region continues to be sparsely populated. Despite having the largest land area of the country, it has the lowest population density at each of the censuses since 1960. Although the density increased from 8 in 1960 to 26 persons per square kilometre in 2000, the rate of increase has been relatively low. This contrasts with the Upper East Region, just to the northeast, and one of the smallest regions, which increased its density from 53 in 1960 to 104 in 2000, making it the fifth densely populated region in the country in 2000. In fact, the Upper East Region is about one eighth of the land area of the Northern Region but with four times the population density, and almost half the population.

The region’s population is dispersed with no significant concentration in specific districts. As in the case of the other two Northern Regions, with relatively prominent population concentration around their regional capital, district, Wa (38.9%) and Bolgatanga, (24.9%), the Tamale municipality also has 16.1 per cent share of the regional population, distantly followed by two other districts, East Mamprusi (9.6%) and East Gonja (9.6%).

On the other hand, two districts, Zabzugu-Tatale (4.3%) and Savelugu-Nanton (4.9%) are rather at the other extreme of the population distribution. The remaining eight districts are within a narrow range of 5.2 to 7.9 per cent of the regional population share. This pattern applies closely to the distribution of both the male and female populations.

The relative slow increase in density of the region’s population is reflected in the stable but slightly declining intercensal growth rate, 3.2 in 1970, 3.4 in 1984 and 2.8 in 2000, which is slightly higher than the national growth rate of 2.7 per cent per annum. The region’s growth rate of 2.8 per cent per annum is however much higher than the growth rate of the sister regions of Upper East (1.1%) and Upper West (1.7%).

The low population density of the region may be the result of the interplay between a harsh climate and ecology, migration and poverty. It may suggest a relatively low population pressure on the land, but in reality, it constitutes a significant and important constraint on the siting of feasible and sustainable community facilities such as schools, health infrastructure, potable water supply, etc.

Age distribution, structure and composition by sex

Age sex distribution

The sex composition of the regional population reflects differential mortality between males and females. At birth, the sex ratio is roughly about 105 boys to 100 girls. A variety of cultural and traditional practices such as preference for boys or girls, may lead to selective female infanticide, or relative neglect of female children, with substantial effect on the sex ratio. There is, however, no evidence of such practices in Ghana. Over the life span, the relatively higher mortality among males leads to a reversal of this ratio at older ages.

The age pattern for both males and females follows closely that of the region as a whole, with slight variations for the age group 0-4 years. Apart from Bole, the percentage of females in this age group is higher than that of males in all other districts. The pattern changes to higher proportions of males at each age group, up to age group 15-19 years. From age 20 years, the proportion of females becomes increasingly higher than that of males, in each district, and at each successive age group, up to age group 35-39 years.

The pattern changes again from age group 40-44 years, to increasingly higher proportions of males, at each successive age group, in all districts, till age 75 years and older, with a higher proportion of males 40 years and older (19.7%) than females (17.7%). This pattern of increasing proportion of males, at older age groups, is contrary to the normal age pattern but is similar to what is observed for the Upper East, Upper West Region, and to some extent, for the Ashanti Region. It is however important to be very cautious in attributing the observed age sex pattern to a higher survival of males at older ages. It rather probably reflects, among others, the patriarchal nature of a population in which older males may tend to exaggerate their age.

The region’s population has gradually changed from a slightly masculine population in 1960, with a sex ratio of 104.0, through 102.1 in 1970 to an almost balanced sex ratio (99.3) in 2000. Apart from the East Gonja District (105.0), which remains at the 1960 level, and three other districts, Gushegu Karaga (94.6), Zabzugu-Tatale (95.5) and the East Mamprusi (96.3), the sex ratio in the remaining nine districts is almost balanced around 99.0 and 101.0.

Age structure and composition

In the absence of any history of catastrophic events, such as wars, epidemics, etc, the age structure of a population typically reflects past fertility and age-specific mortality trends. In a high fertility and high mortality population, the age structure, as captured by a population pyramid, is triangular in shape, with a wide base, indicating high fertility and therefore, high relative proportion of children under 15 years. It tapers off, with increasing age, at the apex, indicating a high death rate, resulting in a relatively small number of adults older than 64 years. Such a population age structure is described as young. By this criterion, the population of the region can be described as young, with 46.2 per cent under 15 years of age.

Although the population aged 0-4 years is high, at least 17.7 per cent in the districts except the Tamale municipality (14.9%), it is however lower than the age group 5-9 years in the districts, except the East Mamprusi District. This strongly suggests elements of fertility decline, however small this decline may be. The same phenomenon is observed for the other two northern regions, the Upper East and the Upper West, although the proportions are higher for the Northern Region.

Apart from the Tamale municipality (29.4%), at least 35.0 per cent of the population are young children, under 10 years of age, in each of the other 12 districts. The proportion in the child dependency age group, 0-14 years, except the Tamale municipality (40.8%), is equally high, in the range of 45.6 per cent in the Yendi, and 49.6 per cent in the East Mamprusi, Districts. The implications are that, more than two out of every five people in the region are children, dependent on others, for their basic needs and care.

The population 15-19 years, which is the higher teenage group, constitutes between 8.0 and 10.6 per cent of the population. This is the age group sometimes treated as part of the working population, but in reality, are teenagers with all the problems and needs of the teenage and younger populations. Together with the population under 15 years, they constitute at least 54.0 per cent of the population in each district, and over 56.0 per cent, in eight districts with the exception of the Tamale municipality (51.4%).

The youthful nature of the region’s population becomes clearer when one observes that the share of the elderly population, 65 years and older, is low, 4.5 per cent, not exceeding 5.6 per cent in any district. The combination of this with a high under 20 year-old population, translates into a median age of 16.8 years, the lowest in the country, and almost the same as that of Upper East (16.8 year) and the Upper West (16.8 years), regions. The implications of such a young population age structure for the provision of social and community facilities, in addition to basic needs for younger people, are many, particularly in view of the poor resources of the region. They also raise issues of youth mobilisation and employment creation to retain the younger population in the region.

The labour force age population, 15-64 years, is at least 47.0 per cent in 11 districts and over half the population (55.2%) in the Tamale municipality and 45.9 per cent in the East Mamprusi District, the lowest for the region. This variation in the labour force population at the district level is also reflected in the variation in the dependency ratio at the district level.

Improvements in health status of the population result in mortality decline, leading to an increase in the proportion of the elderly population, 65 years and older. For the region as a whole, 4.5 per cent of the population are 65 years and older. The range of values for the districts is from 3.8 in the Saboba-Chereponi to 5.6 per cent in the Tolon-Kumbungu, District. The proportion of the elderly population is higher than 5.0 per cent in four districts, Gushiegu-Karaga, Savelugu-Nanton, Tolon-Kumbungu and West Mamprusi.

The ratio of the elderly population to the population of children (0-14 years) is a measure of the relative degree of ageing of the population. The ratio is directly related to the average age of the population; that is, the higher the age the higher the ratio. A ratio of 1.0 indicates equal proportions of elderly to children population. For the region as a whole, this ratio is 9.8 per cent, representing 1 elderly person for every 10 children. The figure varies from 7.7 per cent in the Saboba-Chereponi, to 12.2 per cent in the Tolon-Kumbungu, Districts.

The overall dependency ratio for the region is 103.0 per cent, that is, slightly more than one dependent per worker. For the districts, the figures range from a ratio of 81.0 per cent in the Tamale municipality to 118.0 in the East Mamprusi District. In general, all the districts in the region show markedly high dependency, except for the Tamale municipality (81.0), the Yendi (99.0), and the Bole (101.1), Districts. This is of particular concern, given the very low level of economic opportunities that exist in the region.

Urban and rural population distribution

The rural/urban definition of localities is based on population size. In general, urban localities offer greater economic opportunities and, therefore, attract rural migrants. Unable to afford the higher cost of living in cities, migrants create squatter settlements on the outskirts. These settlements rapidly grow and subsequently encroach on their parent cities, often overwhelming the available services such as water, health care, sanitation, waste disposal, and electricity supply.

Of the 364 urban localities only 27 or 7.4 per cent are in the region.

The Tamale municipality, the regional capital, has remained the third largest urban settlement in the country since 1970. The population of the Tamale municipality has increased by almost 2½ times since 1970, from 83,653 to 202,317 in 2000. It has, however, gradually lost its share of the regional urban population from 42.4 per cent in 1970, when there were only eight urban settlements through 42.0 per cent in 1984 to 40.7 per cent in 2000 when the number of urban settlements in the region increased to 27.

Damongo, Bole and Gambaga are three other important urban settlements that have been losing their regional urban population share since 1970 compared with Karaga and Zabzugu, which have been gradually increasing their share of regional urban population. With the creation of new Districts, a number of settlements were raised to the status of District Capital, to serve as administrative centres while other smaller towns grew as a result of trade and administration. Buipe in particular grew as a result of the Buipe Bridge and the associated trading activities.

Birthplace and migratory pattern

The proportion currently residing in their district of birth varies from 77.0 per cent in the Bole and the East Gonja Districts to 92.0 per cent in the Saboba-Chereponi and the West and East Mamprusi Districts. The proportion born in other districts of the region varies from 4.0 per cent in East Mamprusi, to 18.0 per cent in the Savelugu-Nanton District.

The proportion of those born outside the region varies from 2.0 per cent in Gushiegu-Karaga, to 16.0 per cent in the Bole, Districts. Thus the Bole, and the East Gonja Districts together with the Tamale municipality, have the highest proportion of migrants from outside the region.

Proportion

About 18.0 per cent of the population in the region migrated The figure varies from about 15.0 per cent in the Tamale municipality to about 20.0 per cent in the Gushiegu-Karaga District. Intuitively, one would have expected a much higher proportion for Tamale, the capital and municipal district of the region. A figure of 15.0 per cent suggests a very low level of in-migration, which could be explained by the spill over of the Dagbon ethnic disturbances in the Yendi District. By contrast, the relatively high rate of in-migration into the Gushiegu-Karaga District could be attributed to the relative peace in this district.

Fertility

The mean number of children ever born, to women aged 45-49, also called the completed fertility rate, is a measure of the average number of children a given cohort of women, who have completed childbearing, actually gave birth to during their childbearing years. A comparison between the TFR and the mean number of children ever born is an indication of the extent and direction of fertility change.

The total fertility Rate (TFR) for the region is 4.9 births per woman. This means that a woman, in the region, would have on the average, 4.9 children in her lifetime, if the current schedule of age specific fertility rates were to prevail into the future. The mean number of children ever born is 6.3 for the region.

The TFR at the district level shows a wide variation. The TFR for the Tamale municipality, 3.3, is the lowest for the region, compared with the highest, 5.9, for the Savelugu-Nanton District. In all the districts, the current fertility is lower than the completed fertility rate, suggesting that, if the TFR could be maintained, it would imply a general decline over the years. Fertility is very high in all the districts of the region; for example, the Tamale municipality, with a TFR of 3.3, has a mean number of children ever born (MCEB) of 5.9.

Greater efforts should therefore be made to intensify fertility reducing programme activities, in addition to identifying and addressing fertility sustaining factors in the region.

Mortality

Over the last two decades, the level of child mortality in Ghana has declined substantially, from about 200 deaths per 1000 live births, in the early 1970s, to around 100 per 1000 live births in 2000. These summary figures tend to conceal a great degree of variability among the districts of the region and the various regions. For instance, the 1998 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS) estimated the level of under-five mortality for the Greater Accra Region, at around 62 deaths per 1000 live births (GDHS, 1998), while that for the Northern Region is close to three times this figure, 171 deaths per 1000 live births). These differentials are even wider among districts within the same region.

The indirect estimates of under-five mortality, by district, for the region, for the period centred around 1993. While ideally direct estimates are more reliable than the indirect estimates, the available data do not allow the use of direct estimation. In general, the level of mortality prevalent during the early 1990s, is relatively high throughout the Northern Region, compared with the national estimate. The under-five mortality rate for the East Mamprusi District (165 deaths per 1000 live births), is the lowest while that of the Savelugu- Nanton District (240 deaths per 1000 live births), is the highest mortality level in the region.

|

SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS Introduction Household headship The proportion of households headed by females in the region (14.1%) is much higher than the national average (11.0%). Among the districts, Savelugu-Nanton has the lowest proportion of female-headed households (9.4%); West Gonja (16.1%), Bole (16.7%) and the Tamale municipality (20.1%) have figures in excess of 15.0 per cent. Household size and composition The composition and structure of the Ghanaian household remain largely traditional, even among the most urbanized segments of the society. The complexity and size of the household depends largely on the headship of the household, in terms of both sex/gender and socio-economic status. The more affluent the head of the household, the more complex the household is likely to be. The average household in the region has, on the average, 7.4 members. Of this number, 44.6 per cent are children of the household head and 21.6 per cent are other relatives. The average household size varies from 6.1 in Savelugu-Nanton, to 9.6 in Gushiegu-Karaga. The Tamale municipality, the most urbanized district, has an average household size of 6.5. The relatively high average household size in the region may be a reflection of the housing structure with several round huts belonging to different members of households, on the same compound. The proportion of children in the household varies from 40.3 per cent in the Tamale municipality to 50.8 per cent in Saboba-Chereponi. The proportion of other relatives per household varies from 18.8 per cent in Nanumba to 24.7 per cent in the Yendi District. Thus, households in the region present the same level of structural and numerical complexity as will be expected in very traditional settings. Marital status There is a wide variation in the proportion of the population married in the districts. The Tamale municipality not only has the lowest percentage of the married (54.4%), the highest proportion of the never married (36.9%) but also shares the highest percentage of the divorced (2.3%) with Savelugu-Nanton. By contrast, Gushiegu-Karaga has the highest percentage of the married (70.4%), the lowest percentage of those in consensual union (0.9%), the lowest percentage of the widowed (3.5%), and, in addition, shares the lowest percentage of the never married (22.5%) with Mamprusi West (22.7%). Living together in a consensual union does not appear to be common in the region (1.8%) and is highest in the Bole District (3.7%). Separation of marriages (1.2%), which is also not common in the region, varies within the narrow range of 0.8 per cent in Tolon-Kumbungu, to 1.8 per cent in the Yendi District. Divorce (1.9%) which is also not common in the region, is lowest in West (1.3%) and East (1.2%) Mamprusi. Widowhood, 4.5 per cent for the region, is lower than the national average of 5.0 per cent. Differentials in marital status by sex The Tamale municipality not only has the lowest percentage married for both males (49.2%) and females (59.7%) but it also has the highest percentage of the never married males (45.9%) and females (27.7%). The percentage of the never married males is relatively high in all the districts, ranging from the lowest (32.1% in West Mamprusi and 32.2% in Gushiegu-Karaga) to a high of 45.9 per cent in the Tamale municipality. The high sex differential in the never married is reflected by the fact that the lowest percentage of never married males (32.1%) is higher than the highest percentage of the never married females (27.7%) which, in turn, varies from 13.3 per cent in Savelugu-Nanton to 27.7 per cent in the Tamale municipality. The incidence of consensual union is very low for both males (1.6%) and females (2.0%) and is lowest for both sexes in Gushiegu-Karaga (0.9%) and highest for males (2.9%) and females (4.4%) in the Bole District. Separation of marital relations is relatively very low in the region for both males and females but does not exceed 1.4 per cent for males and 2.1 per cent for females, in any district in the region. Divorce, which is equally low for both sexes, does not exceed 2.0 per cent for males and 2.7 per cent for females, in any district in the region. On the contrary, the differential between male and female widowhood levels is high. The highest level for males, 2.0 per cent in the Bole District, is 2.9 times lower than the lowest level for females, 5.7 per cent, which is in Gushiegu-Karaga. No district in the region has a female widowhood level lower than 6.5 per cent. Apart from Gushiegu-Karaga (5.7%), and the very high level of 10.4 per cent in Savelugu-Nanton, the remaining 11 of the 13 districts have a relatively high female widowhood level, varying within the narrow range of 6.5 to 8.8 per cent. Factors such as polygamy and younger females marrying much older males, who may die early and leave the females widowed, may explain the level of female widowhood, relative to that of males. However, the differential is wide enough and therefore deserves serious concern and appropriate mitigating programme action. This is important and necessary, in the context of the Northern Region, despite the fact that female widowhood level in the region (7.7%) is almost the same as that at the national level (7.8%). On the whole, marital relations are more stable in the region than in the country as a whole. Marital status of children 12-14 years Barely 0.2 per cent of the population aged 12-14 years is married. Those in consensual union, the separated, divorced and the widowed, each constitutes less than (1.0%). The proportion never married is high (99.8%) as expected. The fact that there are 12-14 year-olds already divorced or widowed, may be due to very young girls being married to much older persons, who either abandon them after a while or die while the spouses are still young. At the district level, the proportion married is highest in Gushiegu-Karaga (0.3%) and lowest in the Tamale municipality (0.1%). The proportion in consensual union, separated, divorced and widowed constitutes a small proportion in each district. The proportion never married is high, varying within the narrow margin of 99.7 to 99.9 per cent. Although the percentages on the marital status of children, aged 12-14 years, are not high, they nevertheless depict a rather unacceptable situation where these children are in different marital statuses instead of being in the classroom where they rightly belong. Steps should be taken to ensure that the maximum number possible of children of these ages are in the school system instead of being married. Nationality The distribution of the non-Ghanaian population of the region by district. Overall, the non-Ghanaian population represents only about 2.0 per cent of the population of the region, with 1.3 per cent coming from other ECOWAS countries and 0.02 per cent non- Africans. The numbers are small but vary considerably at the district level. Six of the districts have more than 2.0 per cent of non-Ghanaian population. Tamale, which is a municipality and the capital district of the region, has the lowest proportion of non- Ghanaians. Ethnic strife and social instability, lack of access roads and poor infrastructure could explain the relatively limited penetration of non-Ghanaians into the region. Ethnicity The predominant ethnic group is the Mole-Dagbon, accounting for 52.2 per cent of the population. They represent the largest ethnic group in seven of the thirteen districts of the region. The Gurmas are the next predominant ethnic group, making up 21.8 per cent of the population. They are largely concentrated in seven districts and constitute the majority in three, Nanumba, Zabzugu-Tatale and Saboba-Chereponi. The bulk of the Guan ethnic group in the region is concentrated in three districts, Bole, West Gonja and East Gonja. Islam is the dominant religion, of the region, with 56.1 per cent of the population professing Islam as their religion. Traditional religion is the next dominant faith with 21.3 per cent, while Christians represent 19.3 per cent of the population. At the district level, Islam is the predominant religion of more than 64.0 per cent of the population in seven of the thirteen districts and constitutes over 23.0 per cent of the population in each of the other six districts. Traditional religion and Christianity each constitutes about a third of the population in Bole, Saboba-Chereponi and West Mamprusi. Educational Attainment There is a wide gap in educational attainment between the country as a whole and the region. At the national level, 38.0 per cent (33.1% males and 44.5% females) of the population 6 years and older have never been to school compared with 72.3 per cent (66.6% males and 77.9 females) in the Upper West Region. The district with the lowest percentage of the population that has never been to school is Tamale with 50.8 per cent (42.5% males and 59.0% females). On the other hand, Gushiegu-Karaga has the highest proportion (84.3%) of the population that has never been to school (79.3 per cent males and 89.0 per cent of females). The high proportion of the population of the region who have never been to school, ranging from 42.5 per cent to 79.3 per cent for males and 59.0 per cent to89.0 per cent for females, should be of great concern for the regional administration in particular. Of the population who have ever attended school, 47.5 per cent, made up of 43.6 per cent of males and 53.5 per cent of females, have attained primary school level. About a fifth (21.7%) made up 22.2 per cent of males and 21.1 per cent of females, have attained middle/JSS level. Those who attained secondary/SSS level account for 13.3 per cent (15.7% of males and 10.4% of females) and an additional 4.8 per cent (3.7% males, 4.2% females) attained vocational/technical/commercial school level. About the same percentage of both males and females have attained post secondary school and tertiary levels; the corresponding proportions being 5.1 per cent and 5.5 per cent for males, and 3.9 per cent and 4.6 per cent, for females, respectively. On the whole, the highest educational level attained by majority of the educated in the region, is the primary school (43.6% of males and 53.5% of females). At the district level, the primary school remains the highest level of education attained by a significant proportion of the populations, ranging from 33.8 per cent in Tamale to 52.4 per cent in West Mamprusi, for the males. The corresponding figures for the females vary from 43.6 per cent in Tamale to 64.8 per cent in Savelugu-Nanton. The middle/JSS level, which is the second highest educational level attained in the region, ranges from 17.8 per cent in Gushiegu-Karaga to 26.4 per cent in East Gonja for males. For females, the proportions that have attained middle/JSS level vary from 14.2 per cent in Gushiegu-Karaga to 25.4 per cent in Tamale. The male-female differential increases with higher levels in educational attainment. The proportion of females is higher than that of males for primary school attainment (53.5% and 43.6%, respectively); and this is the case in all the districts. On the other hand, the proportion of males that have attained the middle/JSS level is higher than that of females in 11 of the 13 districts (the exceptions being Saboba-Chereponi and Tamale). Similarly, male attainment at the secondary/SSS level is appreciably higher than that of females in all the districts. While Gushiegu-Karaga is the only district in the region where the proportion of females (4.5%) is higher than that of males (4.3%) for the vocational/technical/commercial attainment. It is also one of two districts (the other being Zabzugu-Tatale), where the proportion of females is higher than that of males for the tertiary level. The analysis shows that there is wide disparity between those who have never been to school at the national level (38.0%) and those in the region (72.3%). The disparity is great between females who have never been to school in the region (77.9%) and those at the national level (44.5%). It is therefore necessary to expedite the implementation of on-going programmes geared towards the improvement of educational facilities in the region to raise the educational attainment in the region, particularly with respect to female education. It is equally important to implement such programmes as will sustain the high achievement at the primary school level, particularly for females, through the JSS to higher levels. Literacy The distribution of the literacy status of the population 15 years and older by district. On average, about 22.0 per cent of the population 15 years and older, are classified as literate. This figure varies from about 12.0 per cent in Gushiegu-Karaga to about 43.0 per cent in the Tamale municipality. East Gonja is the next highest, with about 20.0 per cent literacy rate, considerably lower than the rate for the Tamale municipality. Over all, the proportion literate is 12.0 per cent higher among males than females. ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS Introduction The productive capacity of a country is directly linked with the size of its productive workforce. The legal working age in Ghana is 15 years. The bulk (71.2%) of the economically active population in the region are employed in Agriculture. Only 5.7 per cent of the workforce is made up of Professionals, Administrative or Clerical staff. The rest (23.1%) are in Sales, Services, and Transport and Production. Among the districts, Zabzugu-Tatale has the highest proportion in Agriculture (87.7%). In contrast, the majority of the workforce in the Tamale municipality (53.9%) are engaged in Sales, Services, and Transport and Production. The Tamale municipality also has the lowest proportion of workers in Agriculture (29.1%) and the highest proportion of Professional/ Administrative/Managerial, and Clerical workforce (15.2%). The proportion of males in Agriculture and related activities in the region is higher than that of females in each district. With the exception of the Tamale municipality (39.6%) males and (16.9%) females, the highest percentage of both males (90.3%) and females (85.1%) in Agriculture and related activities are in Zabzugu Tatale (4.2%). The lowest for males (77.5%) is in Yendi and that for the females (38.8%) is in Savelugu-Nanton. Females outnumber males in Sales, Production, Services and related activities at the regional level and in each district in the region. The pattern of occupational distribution of females in Savelugu is particularly worth noting for Agriculture (38.8%), Production and related activities (32.6%) and Sales (22.5%), which three occupations account for 93.9 per cent of all occupations. Industry Nationally, the main industries are Agriculture (52.0%), Wholesale and Retail Trade (15.0%) and Manufacturing (11.0%). The main industrial activity in the Northern Region is Agriculture (70.9%) comprising largely of farming, animal husbandry, hunting and forestry. There is very limited manufacturing (7.1%) in the region. Wholesale and Retail Trading also accounts for only (7.5%) of all industrial activity. Only about (0.7%) of the population are engaged in mining and quarrying activities. A variety of other enterprises in the industry sector, such as Fishing, Hotels and Restaurants, Communication, Health and Education, together comprise 10.0 per cent of the total industrial activity of the region. The proportion of the population in Agriculture is smallest in the Tamale municipality (31.3%). In the other districts, the figure ranges between 62.2 per cent in Savelugu-Nanton to 87.2 per cent Zabzugu-Tatale. The industry sector, (Manufacturing), accounts for less than 10.0 per cent of economic activity in all districts except the Tamale municipality (14.4%), Savelugu-Nanton (14.8%), and Yendi (10.2%). There are very limited mining and quarrying activities in any of the districts. The highest proportion is recorded in Gushiegu-Karaga (1.0%), Bole (1.1%), East Mamprusi (1.0%) and Tamale (1.0%). Wholesale and retail trading accounts for less than 10.0 per cent of all economic activity in all districts, except for the Tamale municipality (24.3%) and Savelugu-Nanton (10.3%). Transportation, Hotels and Restaurants, and other Service activities collectively account for between 7.0 and 22.2 per cent of all economic activity, making this combined sector the second largest source of employment in all the districts of the region. Four main industrial activities can be identified for the region as whole, and for the districts. For the region as a whole, Agriculture, Manufacturing Wholesale and Retail Trade activities are the main industrial activities, in that order, for both males and females. For the males, the order of industries is Agriculture, Manufacturing, and Wholesale trade predominating in eight districts. Agriculture Wholesale and Manufacturing, in two districts and Agriculture Fishing and Whole trade/Manufacturing predominate in the two Gonja Districts, and Agriculture Manufacturing and Fishing in Saboba-Chereponi. For the females, Agriculture, Manufacturing and Sale/Trading predominate in five districts while Sales/Trading and Manufacturing exchange position in four districts. Fishing activities follow Agriculture, with Wholesale/Retail trade and Manufacturing at par, in the two Gonja Districts; Fishing follows Manufacturing and Agriculture in Saboba Chereponi. It is worth noting that males and females both participate actively in Agriculture and Fishing activities in the two Gonja and the Saboba Chereponi, Districts. Employment status Nearly 68 per cent of the economically active population are classified as self-employed, while 22.9 per cent are unpaid family workers; only about 6.1 per cent are employees. This regional pattern is also reflected in all the districts. For example, the proportion of the self-employed ranges from 50.8 per cent in Zabzugu-Tatale, to 79.7 per cent in Savelugu- Nanton. The proportion of unpaid family workers varies from 5.2 per cent in the Tamale municipality to 45.3 per cent in Zabzugu-Tatale. The high level of unpaid family workers, recorded in some of the districts is probably a reflection of the high proportion of the population in the agricultural sector. Employment sector The bulk (83.4%) of the population of the region are employed in the private informal sector. An additional 11.5 per cent are employed in the private formal sector. This justifies the policy to encourage and reinforce the private sector to lead and speed up the growth of the economy. The public/semi public sector accounts for only 4.3 per cent of the working population. At the district level, the proportion of the workforce in the private informal sector varies from 68.8 per cent in the Tamale municipality to 93.8 per cent in Zabzugu-Tatale. The Tamale municipality has the highest proportion of public sector employees (12.0%). In general, therefore, the private informal sector is the largest employer in all the districts. This has very important implications for taxation and revenue mobilisation and collection since those engaged in the informal private sector employment are hard to locate and categorize. |

|

HOUSING AND COMMUNITY FACILITIESIntroduction

The number of rooms available to members of a household, relative to the number of individuals in the household, is an indicator of relative crowding. A crowded house puts additional pressure on available household resources such as water, toilet facilities, food, etc. Overcrowding leads to reduced distances between individuals leading to increased contact and contamination, which provide a fertile ground for the spread of diseases.

Housing stock

The total housing stock in the region is 178,000. Tamale (15.0%) and East Gonja (11.6%) have the highest proportions of the total housing stock. These figures are, in and of themselves, uninformative since they do not take into consideration the population size. In this regard, indicators such as the number of households per house and the population per house, provide a much better indication of the relative adequacy of living space.

The average number of households per house for the region is 1.4. This compares favourably with the national figure of 1.7. The variation by district ranges from 1.1 in Bole to 1.9 in Savelugu-Nanton. The average household size in the region is 7.4 members. The lowest figure is in Savelugu/Nanton (6.1) and the highest in Gushiegu-Karaga (9.6).

For the region as a whole, the average population per house is 10.2 compared with the national figure of 8.7. At the district level, the population per house ranges from under eight in Bole to about 15 persons per house in West Mamprusi. The indications are that at the household level, the region is slightly more crowded than other parts of the country.

Housing condition

Type of dwelling

There are four main types of dwelling units in the region: the separate isolated house or dwelling, the semi-detached house, separate room(s) within a compound usually with common cooking and toilet facilities, and several huts or buildings within a common compound.

The commonest dwelling unit in the region comprises the separate, room(s) within a common compound, which accounts for 53.8 per cent of all dwelling units at the regional level. Among the districts, Yendi (71.6%) has the highest proportion while East Gonja (33.4%) has the lowest. The phenomenon of having several huts/buildings within a shared compound constitutes a tenth (9.2%) but less than a fifth (18.1%) in three districts, West Gonja (12.6), Savelugu-Nanton (17.9%) and Tolon-Kumbungu (18.1%).

It constitutes more than 5.0 but less than 10.0 per cent in eight districts and less than 5.0 per cent in two districts, Saboba- Chereponi (4.8%) and Bole (2.5%). The semi-detached dwelling unit (15.4%) constitutes between a fifth (20.0%) and a third (34.0%) in three districts between a tenth (10.0%) and under a fifth (19.1%) in seven districts and less than 10.0 per cent of dwelling units in the remaining three districts, Savelugu-Nanton (8.0%), Tamale (6.2%) and Yendi (3.4%), the lowest in the region.

The separate house/dwelling unit (17.1%) accounts for between a fifth and a third of dwelling units in three districts, Bole (33.7%), West Gonja (22.5%) and East Gonja (22.7%). It accounts for between a tenth (10.0%) and below fifth (19.8%) in seven districts and below 10.0 per cent in the remaining three districts, East Mamprusi (9.0%), Tolon-Kumbungu (8.8%) and Savelugu-Nanton (7.0%). Other types of dwelling units are dispersed in all the districts of the region, accounting for 2.0 per cent; but not exceeding 5.0 per cent, in nine districts and 5.0 per cent but less than 10.0 per cent in the remaining four districts.

Main material for construction (wall)

A variety of building materials are used in the construction of walls in the region. The major ones include mud or mud-bricks, cement blocks or concrete, sandcrete or landcrete, bamboo, and thatch. The commonest used material for wall construction is mud or mud-brick, which accounts for 82.6 per cent of all materials used for walls. The second most frequently used material is cement or concrete blocks, accounting for 10.8 per cent, while Sandcrete or landcrete accounts for 2.8 per cent.

There is no district, apart from Tamale, where 10.0 per cent or more of walls of dwelling units are made of cement/concrete blocks. In four districts, Bole, West Gonja, East Gonja and Yendi, more than 5.0 per cent but less than 10.0 per cent of dwelling units are constructed with cement/concrete block walls and in the remaining eight districts, cement/concrete blocks walls account for less than 5.0 per cent of dwelling units. Sandcrete is not used much in the region (2.8%) but constitutes about 10 per cent of all walls of dwelling units in Tamale, 3.8 per cent in Yendi, 3.6 per cent in Nanumba and 2.4 per cent in West Gonja. The use of this material for wall construction is negligible in the remaining districts.

Thatch/Palm leaves is rarely used for wall construction only in East (6.5%) and West (3.1%) Gonja and is very negligible as a wall construction material in the remaining eleven districts of the region. The use of wood for wall construction in the region is insignificant, accounting for only 0.6-1.5 per cent of walls of dwelling units.

At the district level, the pattern is similar, with relatively minor variations, except in Tamale, where less than half (48.7%) of the walls of dwelling units are made of mud or mud-bricks and 39.3 per cent made of cement or concrete blocks. In the other districts, the proportion of cement or concrete walls ranges from under 2.0 per cent in West Mamprusi to 8.3 per cent in Bole. Other forms of building materials are rarely used except in Tamale where sandcrete/landcrete is important material for building walls.

Main material for construction (roof)

Apart from Bole (13.2%) and Tamale (23.7%), over 60.0 per cent of dwelling units in the remaining 11 districts are roofed with thatch/palm leaves. On the other hand, while 70.7 per cent of dwelling units in Tamale are roofed with corrugated metal sheet, it is only in four districts, East Gonja (35.4%), Nanumba (30.4%), Zabzugu Tatale (30.2%) and Yendi (31.1%), that over 30.0 per cent are roofed with corrugated metal sheet. In seven other districts, between 10.0 and 29.0 per cent of dwelling units have corrugated metal sheet roof, and less than tenth of dwellings in one district, Gushiegu-Karaga (8.0%).

Bole is unique in the sense that it is the only district in the region with over half (51.1%) of dwelling units roofed with mud/mud bricks in addition to 4.9 per cent roofed with wood. Roofs made with these materials (wood, mud/bricks) do not exceed 2.1 per cent in any other district in the region.

Although bamboo and slate/asbestos are also used for roofing, bamboo accounts for 1.9 per cent only in Gushiegu-Karaga and slate/asbestos are used for only for 3.1 per cent of roofs in Tamale. Whatever the reason for the predominance of thatch roofs in the region as a whole, and mud roofs in Bole in particular, the condition of dwelling units, particularly roofing material, requires concern and serious investment in improved roofing of dwellings in the region.

About 46.0 per cent of the dwellings in the region have earth or mud floor and the rest are made of cement or concrete (52.0%). The figures vary at the district level. The proportion of dwelling units with mud or earth floor varies from 20.7 per cent in the Tamale municipality to 67.0 per cent in the West Mamprusi District. The proportion of dwellings with cement or concrete floor varies from 31.3 per cent in West Mamprusi to over 76.7 per cent in Tamale. Other materials are rarely used for floor construction.

There is not much difference in the use of either cement or earth/mud as a floor material in the districts. In four of the thirteen districts, more than 60.0 per cent of dwelling units have mud/earth floor. On the other hand, cement/concrete is used for the floor of 60.0 per cent or more dwelling units in three districts, and between 40.0 but not exceeding 60.0 per cent in six other districts. In the remaining four districts, the proportion of dwelling units with cement floors is about a third (32.4%) but not exceeding 36.0 per cent.

A higher proportion of dwelling units in rural areas than urban areas in the region have mud/earthen floor. However, in four districts, West Mamprusi (69.2%), West Gonja (67.0%), Tamale (52.4%) and Saboba Chereponi (50.9%), over half of dwelling units in the rural areas have cement/concrete floors. The quality of materials used for flooring residential units needs to be much improved, especially where most members of the household sleep on the floor of rooms.

Housing tenure

In the region as a whole, 85.4 per cent of households own their housing units, 8.7 per cent rent their dwelling units, 5.4 per cent are living rent-free and less than 1.0 per cent are perching.

The proportion of households owning their dwelling varies from 65.5 per cent in Tamale to 95.7 per cent in the East Mamprusi District. The lower rate of home-ownership in Tamale is expected, given the higher cost of buildings in a large municipality as compared with rural locations. Except in Tamale where 27.3 per cent of households rent their dwellings, renting of dwelling units is a relatively uncommon mode of tenure in all districts. Rent-free accommodation and perching are also uncommon, except in Savelugu-Nanton, where 14.8 per cent of households live in rent-free accommodation and 1.3 per cent perch.

Ownership of dwelling unit

Ownership relates to the dwelling unit and not the housing unit. In the region as a whole, 85.4 per cent of all housing units belong to their occupants. Except in Tamale (65.5%), over 75.0 per cent of dwelling units in each district are owned by a household member. Ownership of dwelling units by a relative, who is not a household member (4.5%), is not popular in the region. Apart from Savelugu-Nanton, where about one in eight dwelling units (13.7%) is owned by relatives who are not household members, this category of dwelling ownership does not exceed 6.0 per cent in any of the other 11 districts in the region.

In Tamale, about a fifth (19.9%) of dwelling units are owned by private individuals, not members of a household. This indicates that private individuals may not have the necessary incentives to invest in dwelling units for rent, since dwelling units owned by private individuals, not household members, do not exceed 6.0 per cent in any district in the region. Other types of dwelling ownership, such as employers, corporations, even the government, are not common, except in Tamale, and other district capitals, to a lesser extent.

Number of rooms occupied by households

On average, 36.7 per cent of households occupy six or more rooms, 23.8 per cent occupy four to five rooms, 28.4 per cent occupy two to three rooms and 11.2 per cent of households occupy just a room. At the district level, less than 10.0 per cent of households, in eight districts, occupy an average of one room, compared with over 20.0 per cent of households in Savelugu-Nanton and Tamale. The proportion of households living in two to three rooms varies from 10.5 per cent in West Mamprusi to 41.9 per cent in West Gonja.

Housing facilities

Main source of drinking water

The commonest sources of drinking water in the region are the rain, spring, river and stream (27.2%). About a fifth of households (19.6%) use dugouts for the collection of rainwater, followed by pipe borne water in the form of a standpipe, either inside or outside the house (22.4%) and borehole (17.0%). Other sources, constituting mainly tanker supply, represent only about 1.0 per cent of household water sources. This means that only 39.4 per cent of households have access to potable water (pipe-borne plus borehole); this has implications for water borne diseases for the region.

At the district level, the proportion of households with piped water varies from 0.9 per cent in East Mamprusi District, to 78.9 per cent in Tamale municipality. In most of the districts, the main sources of water are wells, dugouts or rainwater/rain/river/stream. The dependence on these sources of water has major implications for the health of the population. Contaminations during the process of collection may aggravate the incidence of diarrhoea and other water borne diseases. The use of the tanker supply, an important source of household water, is only prevalent in Tamale where it accounts for about 4.0 per cent of the water supply of households.

Main toilet facilities

For the region as a whole, 75.9 per cent of households have no toilet facilities of any sort. Among the districts, the Tamale municipality, with over a third (35.6%) of households, has the lowest proportion of households with no toilet facility. In 10 of the 13 districts, between 80.0 and 90.0 per cent of households do not have any toilet facility. About 14.0 per cent of households in the region use public facilities. In the Tamale municipality, 41.6 per cent of households use public facilities. The two other districts where the use of public toilet facilities is common, are Savelugu-Nanton (19.5%) and Yendi (20.2%).

The use of the water closets (WCs) and the KVIP is very limited. About 2.5 per cent of households in the region have water closets, while 2.3 per cent use the KVIP. Even in the Tamale municipality, only 8.3 per cent of households have access to water closets and 5.3 per cent use the KVIP.

The pit and other types of latrine are relatively uncommon in all the districts. Members of households with inadequate toilet facilities or with no toilet facility at all, are compelled to rely on alternatives such as the bush, farms, etc. This has significant implications for the transmission of infection, and consequently, for the health and well-being of communities, which, in turn, may impact productivity negatively.

Main source of lighting

About 77.0 per cent of households use the kerosene lamp as source of lighting, while 22.0 per cent use electricity. At the district level, access to electricity as source of lighting, varies from 6.9 per cent in Saboba-Chereponi to 58.5 per cent in Tamale.

The distinct advantage of urban areas with regard to lighting is clearly demonstrated by the higher proportion of households in the Tamale municipality (58.5%) that have access to electricity as a source of lighting compared to less than 25.0 per cent in the remaining districts. Apart from the obvious benefits of lighting, the availability of electricity is closely associated with health, economic and social activity and living conditions; for example, cereal and grain mills require electricity.

Non-availability of electricity may influence access to television and radio and, therefore, access to information that may have direct impact on health. On the other hand, availability of electricity may facilitate the use of the refrigerator and, therefore, directly impact storage of food within the household

Main fuel for cooking

About 84.0 per cent of households in the region use wood as a main source of energy for cooking; 11.7 per cent use charcoal and 4.7 per cent use other forms of energy such as electricity and gas. More than 88.0 per cent of households in the districts, except Tamale (45.1%), rely on wood as a source of energy for cooking. On the other hand, 42.2 per cent of households in Tamale, compared with less than 10.0 per cent in the other districts, use charcoal as the main source of cooking fuel.

Other sources of fuel for cooking, used by households in Tamale, which are negligible, (less than 1.0%) in the other districts in the region, are L.P. Gas (4.3%) and electricity (2.7%). At least 1.0 but not exceeding 2.5 per cent of households in the districts, except East Gonja (0.0%), use kerosene as fuel for cooking or at least for starting the fire for cooking.

Electricity, (0.7%), as in general in the country (1.1%), is very rarely used as fuel for cooking, even in the Tamale municipality (2.7%), the regional capital. L.P Gas (1.0%) is equally rarely used as fuel for cooking, even in the Tamale municipality (4.3%). The low use of L.P Gas for cooking needs to be addressed with realistic programme objectives to reduce the very high use of wood and charcoal combined which constitute 95.4 per cent of all cooking fuel in the region. One of the main objectives of such a programme will be, to make available to households in the region, smaller gas cylinders which are not only affordable but will enable L.P.G. to be bought in smaller quantities.

Another element in such a programme would be to widen the use of L.PG by extending its use to lighting and the operation of such household equipments as the refrigerator while at the same time ensuring safety in LPG use. The type of fuel source used by a household may be related directly or indirectly to health outcomes. The poor may use considerably more wood, dung, and other biomass, than the rich. As a result, they may generate high-levels of indoor pollution, leading to increases in the incidence of respiratory illnesses and other health problems.

Lack of utility services implies that many women may spend several hours a day fetching firewood for the household, diverting these women from income generation and childcare activities. The proportion of households who do no cooking, and therefore do not use any cooking fuel, is low (1.4%), as in the Upper East (0.7%), Upper West (0.9%) and the Volta (1.4%), Regions, compared with the Ashanti Region (5.1%), the highest in the country, followed by the Greater Accra (4.8%) Region. The other regions have around 3.0 per cent of households with no cooking.

Cooking space

A cooking space is either a separate room, equipped and intended primarily for the purpose of preparing principal meals (usually referred to as a kitchen) or some other space, used for the preparation of meals.

More than half (53.8%) of households in the region use the open space in their compound for cooking, while 24.4 per cent of households use a kitchen, either exclusively or shared with other households. An additional 17.7 per cent of households use such other spaces as the veranda or a room for cooking. Apart from the 4.1 per cent of households who specifically stated they do no cooking, an additional 2.1 per cent cook but did not indicate where they cook.

At the district level, the distribution of the types of cooking space is generally similar to that at the regional level. The use of a kitchen a separate kitchen exclusive or shared, is commonest in East Mamprusi (48.6%), Bole (46.2%), West Mamprusi (41.7%) and Saboba- Chereponi (34.3%) Districts. The open space for cooking is prevalent in the other districts.

Bathing facilities

In the region as a whole, the shared separate bathroom constitutes a little over a fifth (21.0%) of bathing facilities; the own bathroom for exclusive use is 33.7 per cent and the shared open cubicle (9.1%).

The private open cubicle (14.4%) and the open space (15.5%) each constitutes about one eighth of bathing facilities. Sharing a bathing facility in the form of either a separate bathroom or an open cubicle is common (30.1%) but bathing in a public bathhouse (2.7%), in another house (3.2%) or in a river/pond (0.2%) is rare in the region. There are at least 10.0 per cent of each of the five main types of bathing facility in the districts except, the own bathroom for exclusive use in Gushiegu-Karaga (7.4%) and the open space in five other districts.

The combination of the type of bathing space varies with each district. The own bathroom for exclusive use accounts for 31.1-37.3 per cent in three districts, and 20.0 but less than 30.0 per cent in an additional five districts. On the other hand, the shared open cubicle and the shared separate bathroom, account for between half (50.0%) and over two thirds (68.9%) of bathing facilities in four districts and below a third in only two districts, Bole (30.1%) and Zabzugu-Tatale (28.9%). The private open cubicle, which exceeds a fifth of bathing facilities only in East Mamprusi (23.2%) and Nanumba (22.3%), Districts, accounts for 10.0-18.8 per cent of bathing facilities in the remaining districts. Bathing spaces are well provided for in the region, as reflected in the near absence of public bathrooms and the variety of bathing spaces in all the districts.

Community facilities

Post office facilities

Post office facilities are generally not easily accessible in the region, even in the capital district, Tamale. As a matter of fact, apart from Tamale (7.2%) and two other districts, Savelugu Nanton (2.0%) and Bole (1.1%), all the remaining 10 districts have much below 1.0 per cent of localities having a post office. A post office facility is located within five kilometres in just about a quarter (25.0%) of localities in two districts, Tolon-Kumbungu (25.9%) and Tamale (24.5%), in a tenth but less than a fifth of localities in two other districts, Savelugu-Nanton (18.9%) and Saboba-Chereponi (11.0%) and in 5.0 per cent but not exceeding 10.0 per cent of localities with a post office facility in four districts.

The rest of the five districts have less than 5.0 per cent of localities within a distance of five kilometres. Infact, with the exception of the Tamale municipality (1.4%), Tolon-Kumbungu (15.5%) and Savelugu-Nanton (16.2%), the remaining districts have over 40.0 per cent of localities located 31 kilometres or more from a post office facility.

Telephone facilities

Irrespective of the distance one considers, three districts, Tamale, Tolon-Kumbungu and Savelugu-Nanton, are much better endowed with telephone facilities, relative to all the other 10 districts. The three districts have telephone facilities within about a fifth (20.3%) and a third (34.5%) of localities; over two fifths (43.9%) and two thirds (66.9%) within 10 kilometres while 68.2 per cent in Savelugu-Nanton, 70.2 per cent in Tolon-Kumbungu and 87.0 per cent in Tamale, are within 15 kilometres of a telephone facility. This contrasts drastically with the remaining 10 districts.

For example while three districts Gushiegu-Karaga (1.1%) Zabzugu-Tatale (2.4%) and Saboba Chereponi (4.8%), have less than five per cent (5.0%) of localities with a telephone facility within a distance of 15 kilometres, Bole (32.9%) and Yendi (32.7%) Districts have just under a third of localities with a telephone facility within 15 kilometres and the remaining five districts have just around a fifth (21.1-23.0%) of localities with a telephone facility within the same distance (15 kilometres).

If communities at grass root level in the districts within the region are to be effectively involved in on-going development affecting them, they need to be well informed and have effective means of communicating their ideas and seeking further information. The telephone is one of the best means of such information sharing. The current situation of access to a telephone facility, even in the best-endowed districts, is far from satisfactory in most districts of the region.

Access to mobile phones in the region is very limited due to the lack of an information technology network backbone. Only the Tamale municipality has access to mobile service providers (One touch, Areeba and Tigo). Areeba services have recently been extended to Yendi.

Hospital facilities

The ability of the poor to access facilities that are located at considerable distances is influenced by the road infrastructure and the transportation system. The poor are more likely than the better off to live in remote areas where roads become impassable at certain times of the year. Existing government policy recommendation requires the siting of health facilities within eight kilometres of the localities of residence.

In Tamale, 12.2 per cent of the communities have a local hospital facility compared with all other districts, with only Savelugu-Nanton (3.4%) and Nanumba (3.0%), having around 3.0 per cent of communities with a local hospital facility.

Although the low density of the region (25.9/sq.m), compounded by the scattered nature of localities, makes the siting of community facilities difficult, it nevertheless does not justify the current distribution of hospital facilities in the region. Tamale, which is a municipality and regional capital, however has two thirds (66.8%) of localities within 10 kilometres of a hospital facility and only 3.6 per cent beyond 25 kilometres.

The next relatively better-endowed district with a hospital facility is Savelugu-Nanton with just under a quarter (24.3%) of localities within five kilometres, and under a fifth (18.9%) beyond 25 kilometres. The disparity between Tamale and Savelugu-Nanton Districts, on the one hand, and the other 11 districts on the other hand, becomes clear when one realises that, in most of the other 10 districts, less than 42.0 per cent of localities are further than 25 kilometres from a hospital facility. In fact, in seven of the districts, over 60.0 per cent of localities can access a hospital facility only beyond 25 kilometres. This situation is deplorable, in view of the policy of the Ministry of Health recommends the sitting of health facilities within eight kilometres of localities.

Clinic facilities

As with hospital facilities, existing policy provides for the siting of clinics within eight kilometres of localities. The proportion of communities with a local clinic is lower than 10.0 per cent in all districts, except Tamale, where 19.4 per cent of communities have local clinics.

Although higher proportions of localities are located nearer to clinics than hospitals, the situation is far from satisfactory. The most disadvantaged districts with respect to location of clinics is Gushiegu-Karaga, with 44.2 per cent of localities beyond 25 kilometres of a clinic, followed by East Gonja (37.4%) and West Gonja (39.9%). Five other districts have over 20.0 but not exceeding 30.0 per cent of localities beyond 25 kilometres of a clinic. The disparity with the location of hospitals re-appears, with that of clinics, in the case of three relatively better endowed districts, Tamale (2.9%), Savelugu-Nanton (8.1%) and Tolon- Kumbungu (8.8%), which have less than a tenth (10.0%) of localities beyond 25 kilometres.

Basic health services can be brought nearer to communities through the strengthening of community based health programmes, on the basis of those initiated by the UNFPA/Institute of Adult Education on Mass Media and Adult Population Education (MMAPE). This project trained Adult Literacy group leaders to dispense health/family planning community specific, activities including the dispensation of basic First Aid and non prescriptive drugs, at the local community level.

The distance households have to travel to reach health facilities is an important determinant of the use of health care services. The distance may influence the ability of pregnant women to patronise antenatal care services or for children to access well-baby clinics. Complications arising during labour may also result in the loss of life of mothers when the distance to the nearest facility is too long. In other words, without reliable roads or ambulance services, the health of communities may be seriously affected by the location of health care facilities.

Primary school facility

Existing policy recommends the siting of primary schools within five Kilometres of localities, taking into consideration the population density.

Although the policy of the Ministry of Education on the distance to a basic education facility is far from satisfied, the distribution of primary school facilities indicates that some progress has been made. The Tamale municipality is far ahead of the other districts, with a local primary school facility in over three quarters (78.4%) of localities. All other districts have less than 50 per cent of communities with local primary schools.

There is however a local primary school facility within 40.0 per cent and 50.0 per cent of localities in four districts and within at least a fifth (23.6%) and a third (34.1%) of localities in the other eight of the 13 districts. On the other hand, eight of the 13 districts have between 70.0 per cent and 97.0 per cent of localities with a local primary school facility within five kilometres. Four other districts each have more than 60.0 per cent of localities within five kilometres of a primary school facility, leaving Gushiegu-Karaga, with 57.4 per cent of localities with local primary school within five kilometres

Beyond 15 kilometres, the proportion of localities without a local primary school facility diminishes considerably, to below 5.0 per cent in six districts. The corresponding proportion is 7.6 but less than 10.0 per cent in four other districts and slightly over 10.0 per cent in West Gonja (14.6%), Gushiegu-Karaga (17.0%) and East Gonja (19.6%).

The distribution of primary school facilities in the region is encouraging in view of the dispersed nature of settlements and the low population density of 25 persons per square kilometre. Much more investment is needed to provide more primary schools for the relatively deprived districts such as Gushiegu-Karaga, East Gonja, West Gonja, Nanumba and Zabzugu-Tatale. Provision of school facilities is necessary and essential to ensure that pupils enrol in schools and remain in the education system for as long as practicable.

Junior secondary school facilities

There is a considerable drop in the accessibility and availability of Junior Secondary Schools (JSS) in the region, compared with Primary Schools. Even in the Tamale municipality, the proportion of localities with a local JSS facility is low (21.6%) compared with 78.4 per cent for the primary school facility. Only two other districts, East Mamprusi (12.4%) and West Mamprusi (13.0%) have slightly over a tenth of localities with a local JSS facility. In fact, in four districts, the proportion with a local JSS is lower than 5.0 per cent compared with four districts with the lowest proportion of localities with a local primary school facility between 23.6 and 29.3 per cent.